Municipality of Saranda

The municipality of Saranda is located in an open coastal bay of the Ionian Sea in Southern Albania and its coast is one of the most important tourist attractions of the Albanian Riviera. The territory of Saranda Municipality is 58.96 km2. The municipality was formed with the governance reform of 2015, uniting the former Municipality of Saranda with the municipality of Ksamil. Saranda is accessible by road from three directions: the road coming from Gjirokastra (distance 55 km) which is not in good condition, the coastal road coming from Vlora (distance 124 km) which is very panoramic and in good condition as well as the road from Konispoli with access to Greece at the Qafë Bote border crossing point (distance 42 km), which is a new two-lane road in very good condition.

Delvina

Delvina, the former capital of the Ottoman sanjak in southern Albania, once held significant administrative and military importance, though no historical monuments from that era remain preserved today. This context serves to illustrate the caution required when evaluating the cultural heritage of the Ottoman civilization in any region based solely on the existing preserved monuments.

Finiqi

Finiqi, known for its ancient city of Foinike, stands atop Finic Hill (282 m), east of the village bearing the same name. Positioned at the confluence of the Bistrica and Kalasa rivers in Albania, Finiqi historically controlled crucial natural routes originating from the Gorges of Antigone and Kaonia. These routes passed through the Skërfica and Muzina passes. The city, approximately 7 km from the shoreline, likely utilized the port of Onkezm for maritime activities in antiquity.

Konispoli

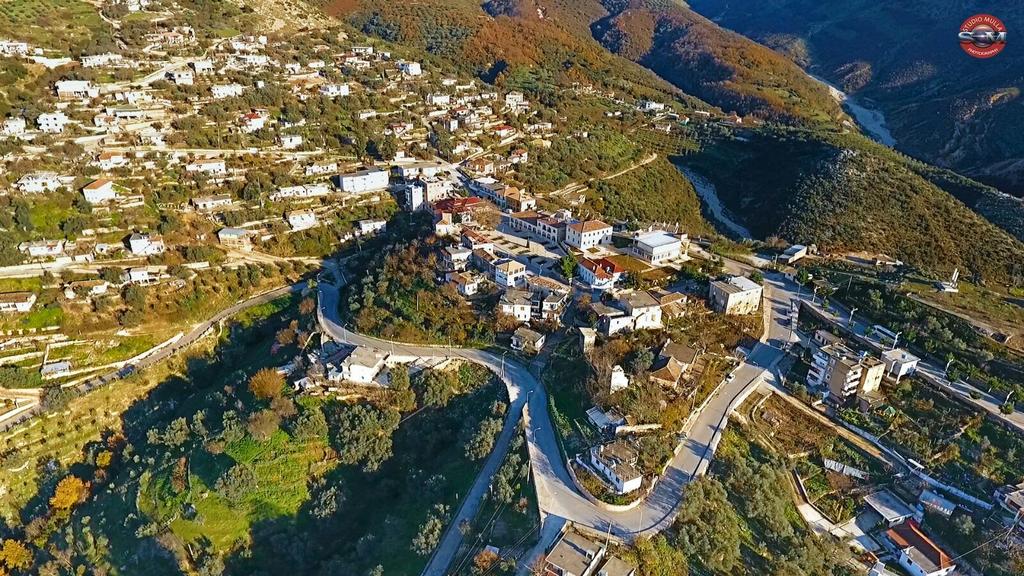

Konispoli is situated at the southernmost tip of Albania, just a few meters away from Greece. The town is located on a plateau divided into four rounded hills with a deep stream. At its foothills lies a unique valley, renowned throughout the Balkans and beyond for its enviable ecosystem and habitat. In ancient times, this area was home to one of the most magnificent cities, featuring castles and typical walls similar to those found in Butrint. Konispoli is often referred to as the twin city of the renowned Butrint, highlighting its historical significance.

History:

Konispol has been inhabited continuously since the Middle Paleolithic period, with a rich civic life spanning all historical eras. Archaeological excavations conducted 3 km west of the city, along the Sterra shore, have unearthed 20 ruins of dwellings, a water well, and pitos (storage vessels) dating back to the 3rd century BC. In the hills of Narta, remnants of an 11th-century BC castle have been discovered, containing the remains of four dwellings. Further west, in Lumbardha, seven preserved dwellings and several tombs from the 12th century have been found. The first written mention of Konispol appears in the 8th century. Following the Turkish invasion, many Albanians from the Konispol region migrated and settled in the village of Hore of Arbëresh in Sicily. During Ottoman rule, Konispol took on the characteristics of an oriental urban settlement.

Onhezmi

Onhezmi first appears in ancient written sources around the 1st century BC, mentioned by Strabo and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and later by Ptolemy two centuries later, who referred to it as a Chaon Cove. Based on their accounts, scholars and travelers such as Pukevili, Liku, Isamberti, and others have debated since the last century whether Onhezmi corresponds to the visible ruins found in present-day Saranda, situated along the scenic Ionian coast of Southern Albania.